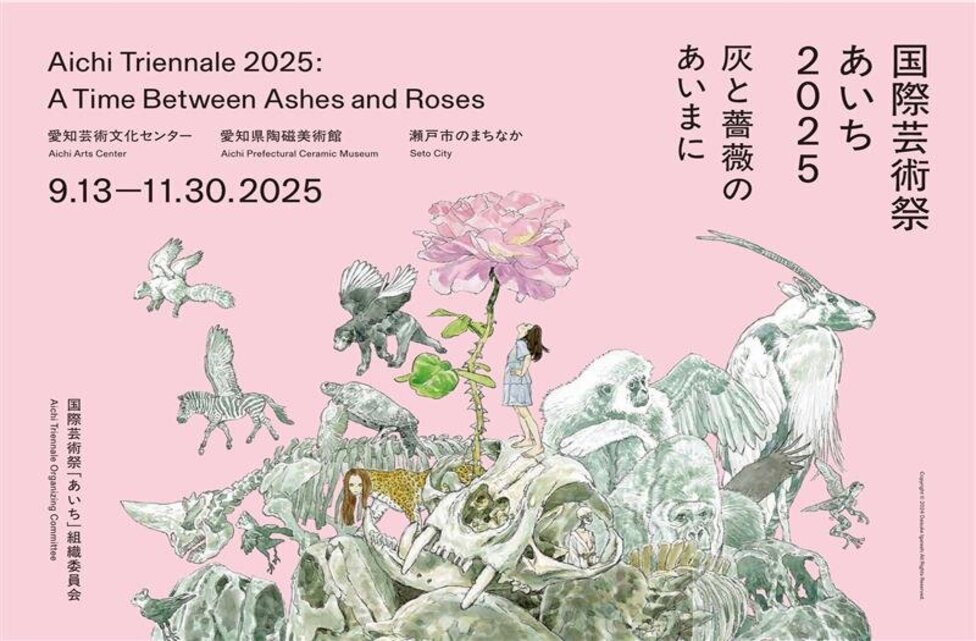

ARTIST TALKS is a PCAI online series of talks and interviews between PCAI Collection artists and other artists, art historians, curators, or art theorists. For the third ARTIST TALK, visual artist Kyriaki Goni talks with curator Daphne Dragona about her artistic practice and recent projects.

he Portal or Let's stand still for the whales, 2020 video still © Kyriaki Goni

he Portal or Let's stand still for the whales, 2020 video still © Kyriaki Goni

“The birds have occupied the center of the city…” one reads as part of which refers to the current covid-19 pandemic. The phrase creates a doubt if this is something experienced somewhere, or a purposely exaggerated image of the very recent past. For almost a year now, while a great part of the human world was asked to slow down, pause, or almost to stand still, the more-than-human world found space to move, live and breathe. Never before had it been more clear that earth’s habitats and ecosystems would be so much better off without us. Half a year after the outburst of the pandemic and as we still have not exited it, one might ask if and how this clear ascertainment will influence the habits and way of life in the future. ‘Nature’ and culture have always been shaping and affecting one another being inseparable and interconnected. The acknowledgement of their inseparability, though, bears a certain responsibility as well as matters of care and ethics. How to deal differently from now on with the constantly evolving ‘naturecultures’ –a term that Haraway introduced with her Companion Species Manifesto–? Which ecologies and forms of relation are yet to be formed, or first imagined? Such questions are at the backbone of the work of Kyriaki Goni who especially examines the role of technology and connectivity in their formations and mutations.

Daphne Dragona, curator

The Flag of Networks Of Trust, 2019 digital print on archival paper mounted on aluminium, 105 x 70 cm © Kyriaki Goni

The Flag of Networks Of Trust, 2019 digital print on archival paper mounted on aluminium, 105 x 70 cm © Kyriaki Goni

Daphne Dragona: Your works have to a great extent a speculative character. Stories taking place mostly in the future invite the audience to realise the footprint of human intervention on the body of earth, and to re-imagine the connection between technological infrastructures and natural ecosystems.

The Aegean Datahaven (2017), for instance, tells a story of a decentralised network of sustainable data havens on islands of the Aegean Sea founded in the year 2082. Their operation is possible thanks to the climatic conditions of the area, and to the well-organised cooperative of islanders that runs them. As we also learn from Networks of Trust (2018-2019), a work that followed, the architecture of the Aegean archipelago plays a decisive role in the communication and mobility between islands, ensuring survival in difficult times. Fiction meets reality, therefore, and the sea is approached as a medium that connects but also divides, as Braudel once also put it.

Why do you choose fiction and narration as tools of your artistic practice? Does your own lived experience influence the shaping of your stories and their narrators?

Kyriaki Goni: I like making stories by mixing up reality and fiction. Fiction is a great way to share thoughts, feelings, desires and fears; it is a device to understand and to question realities, to investigate possibilities, to envision new realities in the present and future, and to find connections with various forms of the past. It is a way to avoid the first person perspective as you get to ‘listen’ to other entities in the narration.

There is a kind of freedom in fiction; it feels like a material that one can sculpt through time and space. Sometimes, I start writing and then I work on the stories as if they were tangible materials, producing at the end expanded multimedia installations. I suppose all these characteristics offer me the chance to investigate the complex notions and worlds I am interested in and to communicate them in a more poetic way to the audience.

Lived experience definitely plays the central role in this process, while simultaneously it is connected to complex socio-political issues. Both works that you are mentioning are based on my experiences on the Aegean islands, my visits, long hikings, observations and discussions with people from islands. I would say that I draw on lived experience in most of my works and then through fiction I open up this experience to something that transcends personal time and space (topos). Lived experience is the main intriegent in shaping the different roles of the narrators, which in each case take the form of a different entity.

The Aegean Datahaven is based on two narrations. The first one is offered by the islanders, who share with the audience an anti-manifesto along with written descriptions of each member island. The second narrator is a traveller of the same period, in the tradition of the travellers in the Aegean archipelago of the 16th-17th century, who produces a series of drawings of the data havens hosted on the islands.

The Aegean Datahaven, 2017 website screenshot © Kyriaki Goni

In Networks of Trust, drawing from my research on dwarf elephant fossils on Tilos island and the discussion with the paleontologist in charge of the excavation there, I wrote the Narrative Poem about the Origins of Networks of Trust, where actually the narrator is an assembly of a fossil and a neural network. The Poem subtly examines geo-morphological changes, insularity and adaptation in the context of networks.

Almost all of my works entail this direct storytelling, and with this at the center they evolve into multilayered expanded installations. Sometimes the audiences are invited to co create the storytelling, as in Networks of Trust. Visiting the installation, people are invited to connect to an offline network running on a secure P2P protocol and to upload their imaginary stories about the possible futures regarding climate crisis, population movement, technology and networks in the area of the Mediterreanean. Part of this collective writing is activated also through workshops with really interesting outcomes. A growing assembly of collective sci-fi stories from various cities and islands is kept carefully in this repository. In the near future I aim to have all stories translated and publish them as an artist book, while also organizing collective readings.

The most recent stories were added during the 5th Istanbul Design Biennale in October 2020. Next stops in 2021 will be the 13th Shanghai Biennale, a group exhibition in Denmark and probably in Perama city in Greece.

DD: In your recent project Data Garden (2020) which was presented as a solo exhibition at Onassis Stegi, you discussed the challenges of storing data in the DNA of living organisms such as the plants. Α fictional story about a tiny endemic plant that grows on the rock of Acropolis became the starting point for a discussion about the relations between human and nonhuman entities and their forms of intelligence and communication.

Plants as organisms that store information for the process of photosynthesis and ensure life on the planet are the protagonists of this story along with a community of users that responsibly and consciously store their private data in plants. The project tells a story of mutual care and interdependence. Data Garden is a work that purposely offers a feeling of hope, but also of slight discomfort.

What does the engineering of plants for data storage really mean? Ethical questions undoubtedly come to the fore when plants are approached as ‘living infrastructures’, and the logic of the instrumentalization of nature appears. How do you handle such questions in your work? Which methods do you choose in your artistic research to avoid scaremongering but also techno-optimism? What is the message that you mostly like to convey through a project like the Data Garden?

Data Garden, 2020 installation view, solo show at Onassis Stegi (2020) © Kyriaki Goni

Data Garden, 2020 installation view, solo show at Onassis Stegi (2020) © Kyriaki Goni

KG: Ethical questions undoubtedly rise when we are discussing Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs). For the purposes of this work, I contacted scientists and scholars who are active in the fields of genetics, cybersecurity, genome editing and synthetic biology etc. The discussions with these researchers became part of the installation. To be honest, I haven’t concluded to any specific answer yet, it is a quite complicated matter.

One can argue that nature has been instrumentalized for centuries now. The question that arises -especially in the post Covid era- is to what extent should or are we allowed to still instrumentalize nature. Scientists say that ‘we are living in the age of pandemics’. They have already warned us that these diseases typically come from animals, spilling over into humans through mingling in disturbed land (mostly by deforestation), fragmented habitats and wildlife markets. As the planet warms up and extreme weather events become the norm, new viruses are appearing more frequently and on a global scale. Now, this situation has affected us in a very direct way threatening our everyday ‘normality’. We have come to realize the extent of exploitation of the ecosystems; we have come to realize that we are part of them and, thus, similarly –if not more– fragile.

Data Garden, 2020 video still © Kyriaki Goni

Data Garden, 2020 video still © Kyriaki Goni

All these decades, especially in the west, we function as if we live alone on Earth, without thinking of the long-term implications of our actions. We produce more, we consume more, we use more natural resources without realizing that they are actually limited. ‘Our narcissism feeds on the Planet’s resources’, says the narrator in the video of Data Garden.

Data Garden, 2020 video still © Kyriaki Goni

Data Garden, 2020 video still © Kyriaki Goni

In the Data Garden, as in any of my works, I avoid offering answers. I rather attempt to create a space of reflection and dialogue instead. I am not interested in a didactic approach through art. Likewise, I do not intend to cause any techno optimistic or techno pessimistic feelings to the audience. Technology is an important part of our daily life, but it is not neutral. It is political, it is about power, about inequalities. And we, as political beings living here and now, ought to pose questions regarding the ways technology is used, and to respectively take precautions.

Data Garden, 2020 video still © Kyriaki Goni

Data Garden, 2020 video still © Kyriaki Goni

Data Garden, integrating my extended research on surveillance, informational self-determination, climate crisis and data economies, discusses the existence of intelligences of different species and simultaneously questions the hierarchies in the western world. Among other parts of the installation, the polyphonic piece created in collaboration with the female vocal ensemble ‘Pleiades’ seeks to underline this multiplicity of intelligences. Within this multiplicity could we create new forms of interspecies care and solidarity, new languages of communication between human more-than-human worlds, new ways of coexisting on Planet Earth? Maybe it’s too late, I don’t know. But it’s worth trying at least.

Data Garden, 2020 installation view, solo show at Onassis Stegi (2020) © Kyriaki Goni

Data Garden, 2020 installation view, solo show at Onassis Stegi (2020) © Kyriaki Goni

DD: Some of your works look into the role that Artificial Intelligence comes to play in the development of science but also in everyday life. Through your projects Eternal U (2016) and Counting Craters on the Moon (2019), you argue that new forms of synergy may emerge based on both machinic and human intelligence; these –depending on the situation– might be challenging, threatening or promising. The contribution of machine learning in the fight against climate change might prove to be of great value. What are your thoughts on this and what role do you think that artistic practices can play in this context? Which narratives and which tools might be of help in an era that artificial intelligence seems to be the common denominator for many solutions being proposed in order to save earth’s ecosystems?

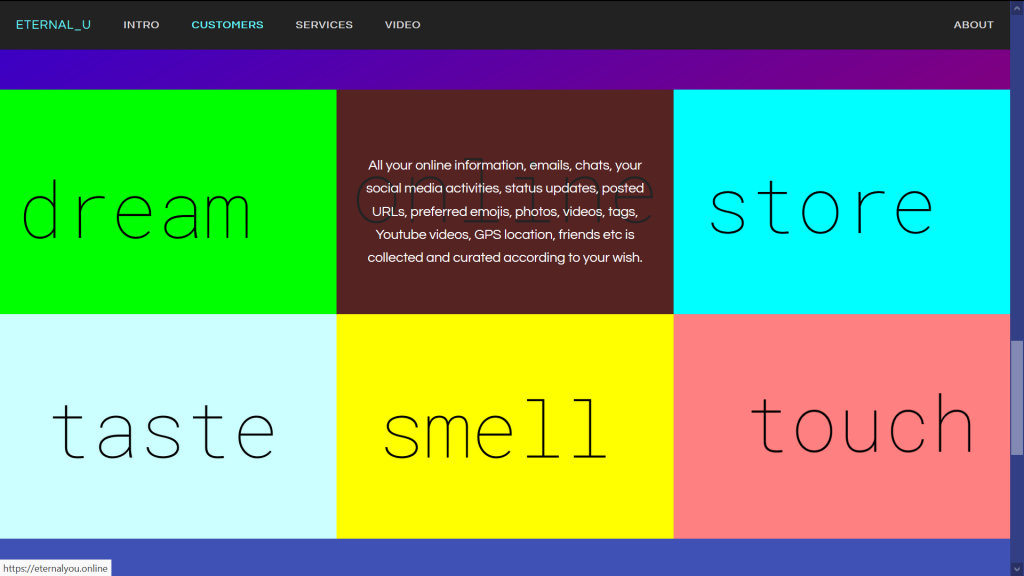

KG: In Eternal U (2016) a video and website installation, I draw from family experience of Alzeihmer’s disease and I build a fictional company that offers trainable AI systems as a substitute for the patient’s lost memory. On the company’s website one can find the perfect fit to satisfy the personal memory needs. In one of the cases, as a result of a malfunction, the trained bot claims digital personhood. The work deals with notions of memory both in digital and physical forms on the one hand, and with human-machine interaction in the context of surveillance, bias, rights and digital personhood on the other.

eternal_u, 2016 website screenshot © Kyriaki Goni

eternal_u, 2016 website screenshot © Kyriaki Goni

Counting Craters on the Moon (2019) a multimedia installation presents an imaginary encounter between the third director of the National Observatory in Athens and acclaimed astronomer Johann Friedrich Julius Schmidt (1825-1884) and the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) DeepMoon, both of which set out to count the craters on the moon. I collaborated with the scientific team that developed DeepMoon in the Canadian Institute for Theoretical Astrophysics and the University of Toronto, as well as the National Observatory here in Athens speculating upon the possible synergies between human and machine. I tried to imagine how we can learn from and with machines in order to build different, multiple and, possibly, collective understandings of the surrounding world and its cosmos.

Counting Craters on the Moon, 2019 installation view, solo show at Aksioma (2019) Photo by Janez Janša

Counting Craters on the Moon, 2019 installation view, solo show at Aksioma (2019) Photo by Janez Janša

I believe that machine learning, just like other other technological tools as well, can indeed be of great help in the fight against the climate crisis. These systems can process vast amounts of data and offer predictions and solutions by simulating possibilities. But we have to remain vigilant regarding two aspects. The first one is; Who owns these technologies and for whose sake do they offer solutions? Take for example the waste management- nothing to do with AI, but it offers a glimpse to the western mentality; some European countries pay countries in Asia to take their waste. This does not make sense, since it does not confront the problem at its roots, and as a consequence creates environmental inequality.

The second aspect is the carbon footprint that these technologies leave behind. To mine huge datasets, to run models one needs great amounts of CPU (Central Processing Unit). And of course we arrive again to the previous point, namely to who owns the power and the financial resources to support these infrastructures, preferably of course on distant grounds with low paid staff, to minimize the environmental consequences.

Counting Craters on the Moon, 2019 installation view, solo show at Drugo More (2020) Photo by Tanja Kanazir

Counting Craters on the Moon, 2019 installation view, solo show at Drugo More (2020) Photo by Tanja Kanazir

Art can and does play a role, as a medium of raising awareness and offering a space of discussion. Having said that I don’t get the artworks, which in order to do that, they themselves use technologies that intensify the very same problems. This is something that puzzles me.

DD: At the video The Portal or Let's stand still for the Whales (2020) that you produced as a commission for PCAI, two different narratives form one story. One refers to how life of urban dwellers has been affected by the pandemic, and the other –as previously mentioned– refers to how more-than-human worlds benefited from it, referring specifically to the reduction of noise pollution. Two different stories come together to express the deep connection between human and more-than-human worlds for a healthy life on the planet. I read recently in the Guardian an article about the pandemic emphasized exactly that. There is one global health; people’s health is intimately connected to the health of wildlife, the livestock and the environment.

How has the Covid 19 pandemic affected your artistic work and way of thinking? Is there something to win or to take from this generalised crisis that we are all experiencing which is economic, sociopolitical, environmental and a crisis of care at the same time? Can knowledge on living and technological networks be of help at this very moment?

KG: The pandemic has affected me like the majority of art practitioners in terms of scheduling, since the work in the studio is anyway a quite solitary condition. My solo show Data Garden last September did not open properly for the audience in Athens, having already been postponed once in the first lockdown. Modern Love (or Love in the age of cold intimacies), a group exhibition curated by Katerina Gregos at the Museum fuer Neue Kunst in Freiburg where my work The Portal or Let’s stand still for the whales along with The Perfect Love #couplegoals commissioned for the exhibition are hosted, closed shortly after its opening due to Covid-19 measurements with most works now being presented online.

The art sector has been heavily impacted by the pandemic, and it urgently needs to be supported accordingly. After all, art is a vehicle for people to imagine, to question, to be open to otherness. It is very much needed now, in times of great social, political and economical tensions.

Surveillance, digital existence, instractructures and networks etc are at the epicenter of my research for years now. The pandemic didn’t change that, but I feel that these subjects are now brought into attention due to the pandemic and its consequences. A certain awareness of fragility and interdependence on a planetary basis are maybe the two things that became even clearer to me due to this situation.

In this context of course we can talk about global health and this pandemic revealed its fragile structures, both on an environmental and an infrastructural level. The critical question is what do we get from this situation on a deeper level of understanding and sentience.

This crisis highlights our perpetual interdependence with our environments. Until now we acted as though our biotic and abiotic infrastructures could endlessly care for us. Now, we must realize we need to care for them in return. We need to accept and recognize the importance of reciprocal care and maintenance on a long-term basis for the ecosystems that contains us. Of course knowledge on living and technological networks can help with that, and I believe art can contribute to this knowledge. To start thinking and acting as part of these ecosystems is difficult and overwhelming, so maybe we should go step by step. Being conscious members of the broader networks could even start from small things in our household, and think about how we maintain our appliances, devices, apparel, to give a basic example.

But it is also our mentality that has to change, the way we perceive ourselves in relation to the cosmos. Sometimes I attempt to think what it feels like to be a tree in a forest in a wildfire, or to be a blue whale troubled to make my way in an ocean full of human made noises. Thinking of the other living entities certainly offers perspective in your everyday life and choices.

Daphne Dragona is a curator and writer based in Berlin. Through her work, she engages with artistic practices and methodologies that challenge contemporary forms of power. Among her topics of interest have been: the controversies of connectivity, the promises of the commons, the challenges of artistic subversion, the instrumentalization of play, the problematics of care and empathy, and most recently the potential of kin-making technologies in the time of climate crisis. Articles of hers have been published in various books, journals, magazines, and exhibition catalogs by the likes of Springer, Sternberg Press, and Leonardo Electronic Almanac. She has collaborated with institutions such the Onassis Stegi, Laboral, Aksioma, NeMe, EMST (National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens), Akademie Schloss Solitude for the curating of exhibitions, workshops, conferences or other cultural events. Dragona was part of the core curatorial team of the transmediale festival trom 2015 until 2019. She holds a PhD from the Faculty of Communication & Media Studies of the University of Athens. daphnedragona.net

Kyriaki Goni is an Athens born and based artist. Working across media and technologies, she creates expanded, multi-layered installations. She connects the local with the global by critically touching on questions of surveillance, distributed networks and infrastructures, ecosystems, human and other than human relations. Her work is presented in solo and group shows (13th Shanghai Biennale, PCAI, Modern Love, 5th Istanbul Design Biennale, Aksioma, Onassis Stegi, Transmediale, The Glass Room San Francisco). Her work Data Garden (2020) won the INSPIRE Prize2020 from the Metropolitan Organization of Museums of Visual Arts of Thessaloniki – MOMus. She is a Delfina Foundation alumna (2019) and an Artworks SNF fellow (2018). She writes (Leonardo 49:4, Neural #65 etc) and teaches frequently as part of her ongoing research within artistic practice. With prior graduate studies in Fine Arts and Social Anthropology, Goni also holds an MA in Digital Arts and an MSc in Cultural Anthropology. kyriakigoni.com